»SYMPHONIA HUNGARORUM« A THOUSAND YEARS OF HUNGARY’S MUSICAL CULTURE

Exhibit in the Budapest Historical Museum

Buda Castle

30 March–29 October 2001

Organizers:

Budapest Historical Museum

Hungarian Musicological Society

National Széchényi Library

Hungarian National Museum

Compiled and edited by

JÁNOS KÁRPÁTI

Assisted by

ÁGNES GUPCSÓ

Authors and scholarly cooperators

ANDRÁS BATTA, LÁSZLÓ DOBSZAY, MÁRIA ECKHARDT, LÁSZLÓ EŐSZE, ZOLTÁN FARKAS, LÁSZLÓ FELFÖLDI, ILONA FERENCZI, MELINDA KABA, PÉTER KIRÁLY, JÁNOS MALINA, GÉZA PAPP, BÁLINT SÁROSI, FERENC SEBŐ, LÁSZLÓ SOMFAI, MÁRTA SZ. FARKAS, JANKA SZENDREI, KATALIN SZERZŐ, TIBOR TALLIÁN

Musical program edited by

ANDRÁS SZÉKELY

Designed by

GYULA KEMÉNY

Translated by

ERZSÉBET MÉSZÁROS

Revised by

PAUL W. MERRICK

|

|

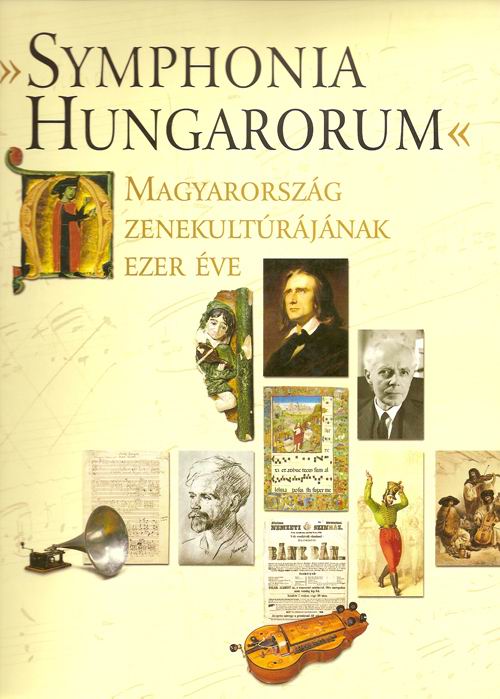

Bishop St Gerard’s legend

The episode of St Gerard’s legend dating from the 12th century is the first written document of the history of Hungarian music. The maid servant turning the handmill was evidently singing some kind of Hungarian worksong.

Continuoque mulier, que molam trahebat, cantare cepit. Admirans autem episcopus, dixit ad Waltherum: “Walthere, audis symphoniam [H]ungarorum, qualiter sonat?”

Then the woman, who was turning the mill, started to sing. The bishop said to Walter wondering: “Do you hear, Walter, how the symphony of the Hungarians sounds?”

St Gerard’s major legend in the Mondsee Codex,15th century

Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Cod. 3662

Through the intermediary of the three characters – the bishop, the musically trained companion and the peasant woman singing a folksong – the legend bears evidence of the meeting of Christianity and high musical culture with spontaneous Hungarian musical expression. It is a symbol of the appearance of the Hungarian music in Europe and, at the same time, the point of departure for the thousand-year-old history of musical culture in Hungary.

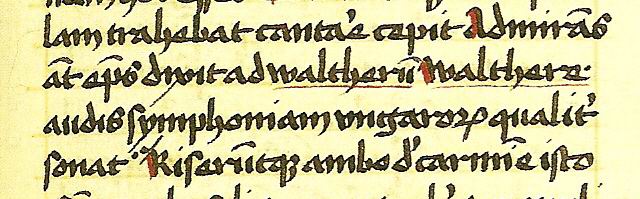

»Hungarian Gregorian Chant«

When the Magyars adopted Christianity and introduced the Roman liturgy to the country, they made Gregorian plainchant the foundation of their culture. It meant using a combination of the highest-level art music and the traditional music of the time, supported by sources of Southern Europe and the Middle East and rooted simultaneously in the theory of the classical Graeco-Roman concepts of music. It did not mean taking over a complete, consolidated musical repertory but a living idiom, itself in the process of development, and requiring active participation. On the evidence of the surviving codices the repertory of the Gregorian liturgy, adapted in Hungary and gaining wide currency through the surprisingly well developed education system, was characterised by the superposition of general, regional and local variants.

Benedictional of Esztergom, last quarter of the 11th century

Zagreb, Metropolitanska Knjižnica Zagreb MR 89

Pontifical of Veszprém, 14th century Budapest, National Széchényi Library Clmae 317

Antiphona: Advenerunt nobis–Schola Hungarica, László Dobszay (Hungaroton)

Troubadours and minnesingers at the royal court

Political and dynastic relationships had greatly influenced the secular musical culture of the European royal courts since the Middle Ages. Queens born in foreign countries brought to Hungary their own households – a large group of knights, musicians, servants, and entertainers –, introducing thereby new customs, fashions and culture.

Jacques Barbireau: Der pfoben swancz, Camerata Hungarica (Hungaroton)

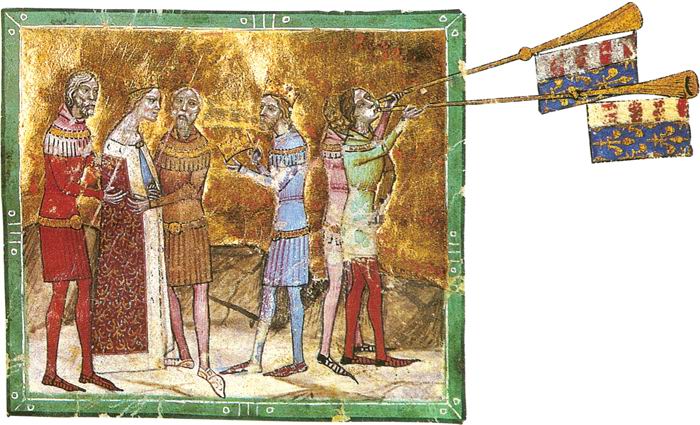

Trumpeters at the wedding of Charles Robert (1288–1342) and Elisabeth.

Miniature from the Illuminated Chronicle, second half of the 14th century

Budapest, National Szcéchényi Library Cod. lat. 404

Charles Robert married the daughter of Wladislas I, King of Poland in 1320; she became his third wife. Standing with their back to the king two trumpeters

blow their instruments ornamented with flags.

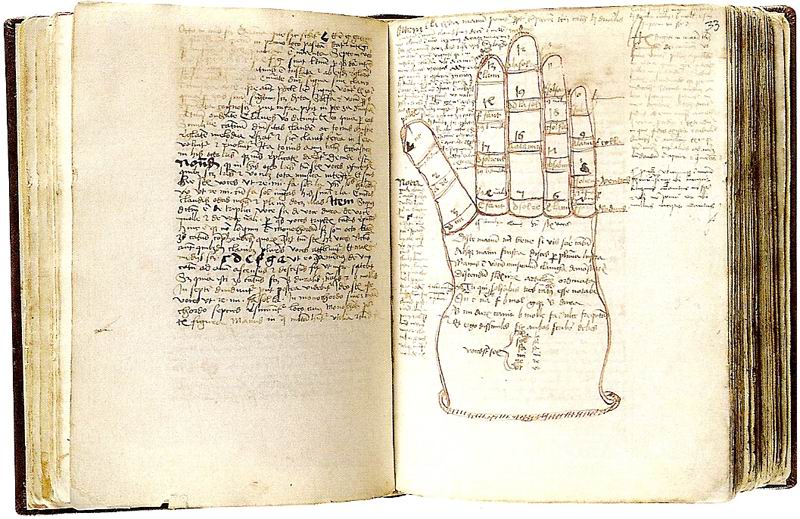

László Szalkai’s schoolbook, 1490

Esztergom, Cathedral Library, Mss. II. 395

The composite volume preserves the subject-matter of instruction at the parish-school of Sárospatak. It was compiled by the one-time student, later archbishop of Esztergom László Szalkai under the guidance of his teacher János Kisvárdai who had been trained in Cracow. The section on musical theory contains an anonymous Central European-type tract and a tonary. The melodies included as examples suggest the influence of Cracowian Gregorian chant tradition transmitted probably by the university whereas the notated lines in Szalkai’s hand are in cursive Hungarian notation. The picture shows the Guidonian hand and solmization exercises.

Chroniclers of the Turkish Occupation in Hungary

The rapid expansion of the Turkish rule jeopardised the overall prosperity of the whole Europe but its consequences were felt in Hungary in the first place. The disaster of Mohács (1526) and the tragic death of King Louis II were followed by the election of two kings at the same time which, together with the establishment of the Ottoman power and the Habsburg expansionism led to the disintegration of the country into three parts. The capturing of Buda Castle by the Turks (1541) determined the course of development of the Hungarian economic and cultural life for nearly one hundred and fifty years.

Verse chronicles (historical songs) represented a special genre of the varied and rich literature which developed from that time on in written form, even if as a continuation of the medieval minstrels’ oral tradition. The development of book-printing contributed to its spread. Their hey-day was the 16th century, from which about one hundred and fifty written documents survive.

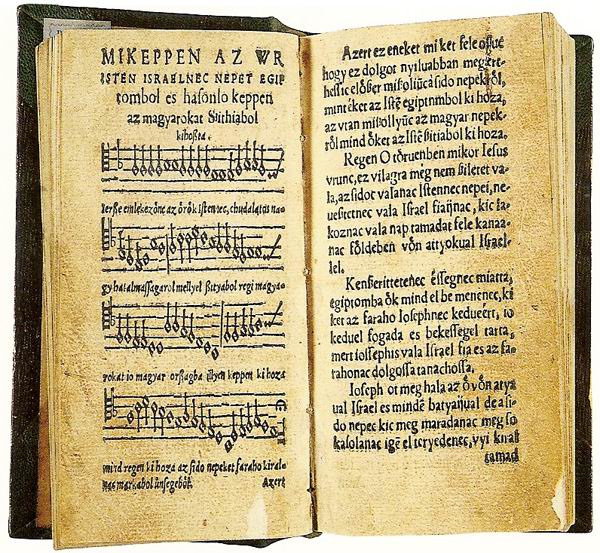

This collection is named after György Hoffgreff, a printer in Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca). The songbook contains 25 Biblical stories, its dated items originating from between 1538 and 1552.

Hoffgreff songbook

Kolozsvár 1556

Budapest, Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Collection of Manuscripts and Old Books, RM I. 8-r, 211

A Virtuoso from Hungary of International Fame: Valentin Bakfark

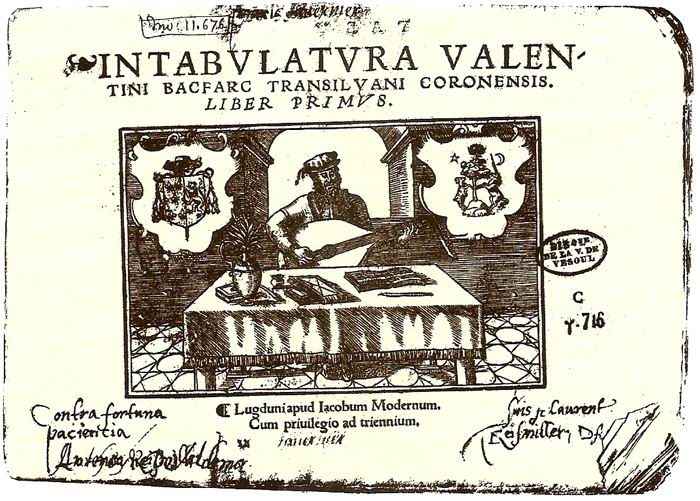

The lutenist Valentin Bakfark is mostly known by the Hungarian form of his name Bálint Bakfark. Born in Brassó (now Braşov), Transylvania, he belonged to the intellectually most outstanding representatives of the era of Renaissance in Hungary whose artistic accomplishments can only be measured with those of his contemporaries abroad.

The title-page of Bakfark’s first lute edition

Intabulatura Valentini Bacfarc Transilvani Coronensis Liber Primus

Lyon 1552

Bibliothèque municipale, Vesoul

Bakfark: Fantázia III à 4, Lutz Kirchhof (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi)

Music in the Reformation and Counter-Reformation

In the first half of the 16th century the Reformation, the expansion of the Turkish rule and the bad economic situation had an unfavourable effect on the state and functioning of the medieval Church and schools. Music lost much of its importance within the weakened institutional framework. The Turks occupied the major cultural centres and the patrons of musical life fled from the occupied territories. The disintegration of the medieval frames of musical usage and the gradual headway, then spread of the Reformation went hand in hand with the emergence of new possibilities, new musical and book genres – psalm paraphrases and song-books.

The music at the age of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation can chiefly be demonstrated by means of material that originated in and survived outside Hungary’s present-day borders – in Upper Hungary now belonging to Slovakia and in Transylvania now belonging to Romania.

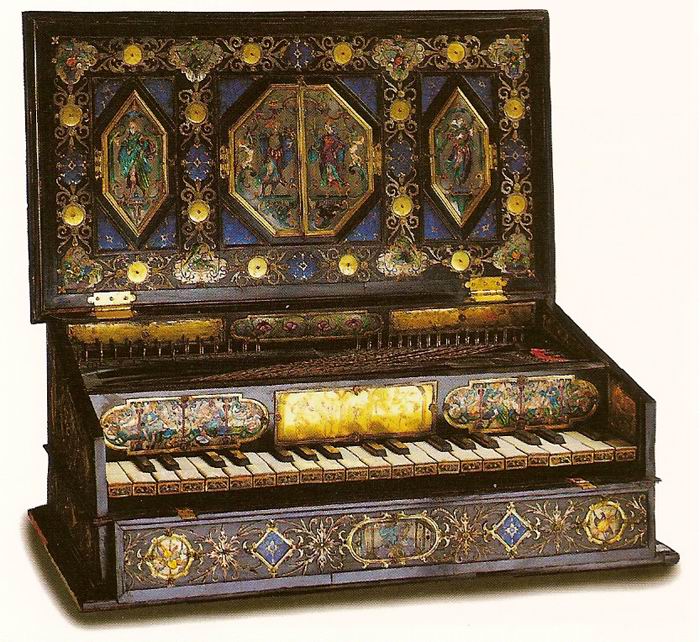

Virginal from the property of Katherine of Brandenburg (1604–1649)

617, probably Augsburg

On the evidence of tradition and surviving inventories it is highly probable that this instrument had once been owned by the second wife of Gábor Bethlen, Prince of Transylvania.

Music at Prince Esterházy’s Court

From the late 17th century onwards the most important patrons of music in Hungary came from aristocratic circles with exceptional means at their disposal. Persons with lively interest in music could be found in almost each branch of the large Esterházy family. The Esterházy court played an important role in the history of music since it acted as a “workshop” for the creation of Joseph Haydn’s symphonies and string quartets and as a “platform” for their performance. It enabled Haydn to leave behind the bounds of court hierarchy and become an independent composer, a celebrated artist of the London concert halls, and an eminent representative of the musical life of the whole Continent.

Prince Nikolaus Esterházy’s (1714–1790) favourite instrument was the baryton, a large-sized viol similar to the cello. At the beginning of his court service Haydn composed about 175 works for the prince and his unusual instrument.

Baryton from the property of the Esterházy family

Joann Joseph Stadlmann, Vienna, 1750

Budapest, Hungarian National Museum, cat. No. H. 1949.360

The Music of Towns in 18th-Century Hungary

During the 16th-18th centuries a town’s status, denominational affiliation and the composition of the nationalities living there determined the nature and standard of its musical life. The royal free boroughs, which belonged under the king’s suzerainty, had their own special rights, self-government and jurisdiction. Of all the cathedral towns Győr had the most flourishing musical life. András Mechler, the master of the chapel for half a century (1711–1765), laid the foundations for high standards in cathedral music. He was succeeded by Benedek Istvánffy, one of the most talented composers of 18th-century Hungary, who was in charge of the ensemble between 1766 and 1778. His two Masses and ten minor church music works bear evidence of his excellent sense of form and familiarity with the most progressive stylistic trends of his time.

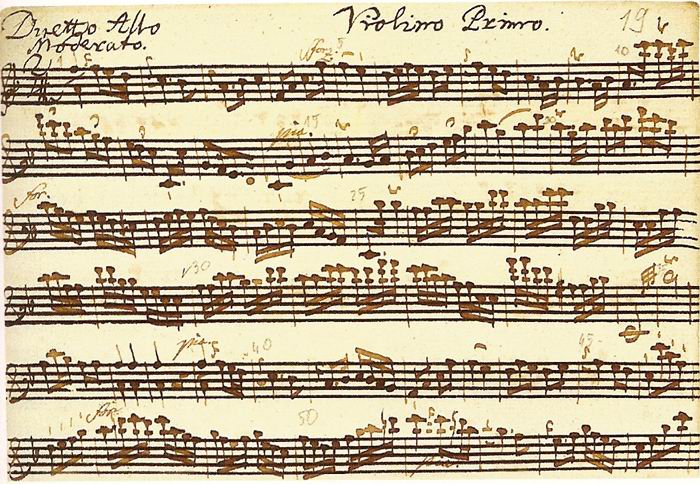

Benedek Istvánffy (1733–1788): Offertorio Veni sancte Spiritus

Violino primo

Hungarian Dances – from the Ungaresca to the Csárdás

The first piece with an allusion to Hungarian character appeared with the title Hayduczki, i.e. hajdú dance in a Polish collection with organ tablature in the mid-16th century. Not much later a piece entitled Ungarischer Tanz emerged in a lute collection published in Strasbourg (1556), a Passamezzo ungaro in another lute book of Leuven (1564), and an Ungarescha Saltarello in a German organ tablature (1583). By virtue of their peculiar structure and their accompaniment reminding of the folk practice of bagpipe music, these dances can be regarded as documents of the Hungarian music, even if they were created abroad on the model of Western European dances such as allemanda and padovana. The wealth of material in Hungarian sources (the Kájoni Codex, Stark’s Virginal Book of Sopron, the Lőcse and Vietoris Tablature Books) support their significance.

Verbovačka (recruiting) Upper Hungary, about 1760

Anonymous master

Rimavska Sobota (Rimaszombat) Gemerské Múzeum

It features the male solo dance reflecting the traditional taste of the time and the alluring, jumping dance in pairs – danced by Hungarian hussars and women – along with the country dance widespread in the 18th century, danced by the Austrian cuirassiers and their partners. The anonymous painter stressed the difference in the dances by using different musicians: the hussars’ dance is accompanied by a gypsy band, the cuirassiers’ dance by Jewish musicians.

National Theatre – National Opera

Ferenc Erkel’s thorough knowledge of opera and his exceptional talent as a composer made him suitable for creating the national opera. He chose from the international assets of the genre with a safe hand the types adequate for national aspirations with regard to dramaturgy and composition at his first attempt and adapted them to the heroic-tragic topic of the Hungarian drama. Bánk bán, which was given its premiere in 1861, is the paradigm of the classical Hungarian national opera. The noble Hungarian tone creates the national character of the persons in the opera, and thereby the national ethos of tens of thousands who let the voice of the heroes resound in themselves.

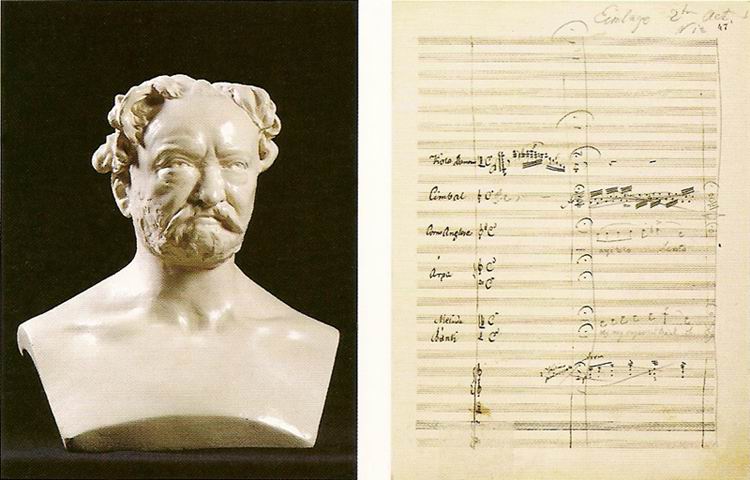

Ferenc Erkel (1810–1893) bust by Alajos Stróbl

Budapest, National Széchényi Library, Music Division

Melinda’s scene from the 2nd act of Bánk bán, autograph score

Budapest, National Széchényi Library, Music Division

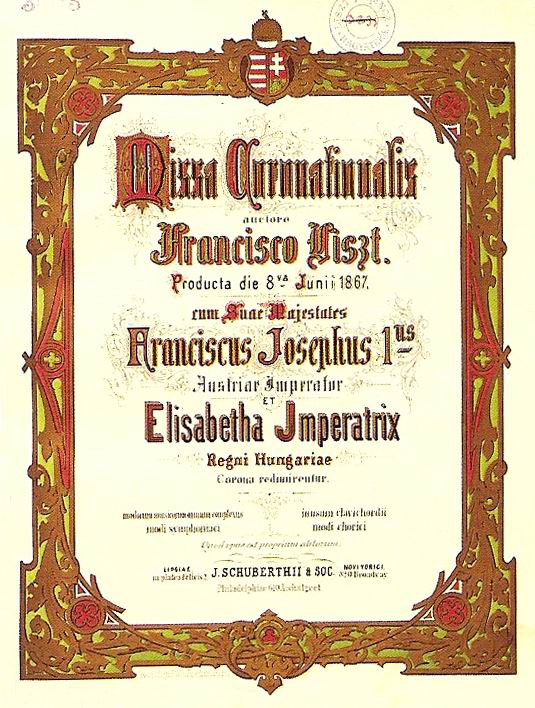

Ferenc Liszt on the Road to Hungarian Music

His two grandiose oratorios bear direct Hungarian relevance. One of them, The Legend of St Elisabeth is about the Hungarian-born saint, who lived in Thuringia. The other one is the the Coronation Mass (1867), in which “the ecclesiastical and Hungarian national characters find their clear expression”, as Liszt wrote to Mosonyi. The performance of the Mass had once again symbolical significance: almost all Hungarian musicians joined forces to achieve that at the coronation of Austrian Emperor Francis Joseph and Empress Elisabeth to the king and queen of Hungary, the music of Liszt should be performed.

Franz Liszt (1811–1886): Coronation Mass, title page of the first edition

Budapest, Liszt Ferenc Memorial Museum LH 3663

Liszt: IX. Hungarian Rhapsody, Kornél Zempléni (Hungaroton)

Musical Life in the Period of the Dual Monarchy

With the Compromise of 1867 Hungary gave up its national independence, one of the demands of the 1848 War of Independence and received in exchange an almost equal co-power in the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy as well as possibilities for the development of its industry and trade holding out promises of overcoming the centuries-long backwardness. In 1873 Buda and Pest, the two towns lying on the opposite banks of the Danube were united and started to grow rapidly as the capital of Hungary so that within short Budapest could enter into competition with Vienna, the other capital along the Danube.

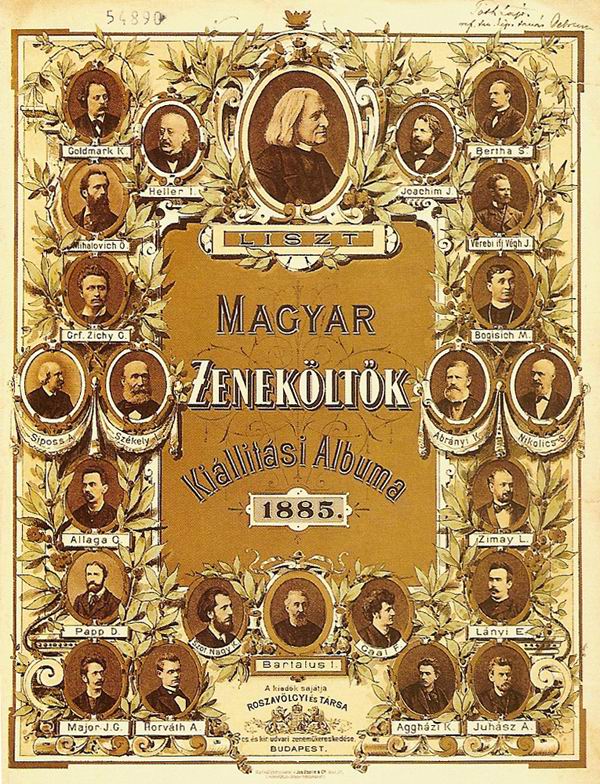

Exhibition Album of Hungarian Composers, compiled by István Bartalus (1821–1899)

Budapest 1885, Rózsavölgyi

Budapest, National Széchényi Library, Music Division 54.890

Gypsy Musicians – Hungarian Popular Music

„…Bihari earned Gypsy music a fame for that cannot be surpassed. Though the Hungarian nobility had long been protecting and praising it, it was through him that Gypsy music became an integral part of national representation. To a certain extent it became attached to the obligatory ceremonies of the Diet at Pozsony; as a national art it found access to the coronation ball … In the years between 1805 and 1825 Bihari gave the Gypsy music such a splendour that even Vienna was enthusiastic about.”

(Ferenc Liszt: On Gypsies and Gypsy music in Hungary, 1861)

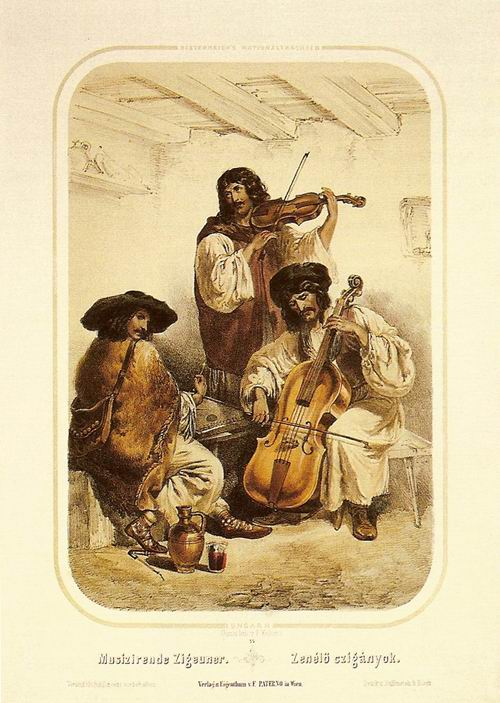

Gypsies playing music in the 1850s

Franz Kollarz (1829–1894)

Coloured lithograph

Budapest, Hungarian National Museum, Historical Portrait Gallery T 4531

János Bihari’s song „Mikor a pénze elfogyott” , Lajos Boross’ band (Hungarian Radio)

Austro–Hungarian Operetta and Musical Comedy

Musical entertainment between 1840 and 1880 was dominated by népszínmű (a 19th-century play about peasants with popular-style art music), which was where Hungarian musical theatre as entertainment originated. The composers portrayed village life and its typical figures for town audiences of frequently non-Hungarian descent.

A contributory factor in the unparalleled success of János vitéz (John the Valiant), the “most typical Hungarian operetta” was that the composition of the work occurred right in the middle of the most frenetic cult of the actress Fedák. Once again, a prima donna was assigned the leading male part, leading to victory the “second” János vitéz (the first, Petőfi’s poem, had long been a set book in schools) at the Király (Royal) Theatre. It is less an operetta, than a Singspiel.

Pongrácz Kacsóh (1873–1923): János vitéz [John the Valiant] –

Sári Fedák (1879–1955) acting as John the Valiant, Vilma Medgyaszay (1885–1972) as Iluska,

18 November 1904, Király Theatre

The Discovery of the Peasants’ Music

The scientific foundations of up-to-date folk music collecting methods were laid by the linguist-stenographer Béla Vikár in an exemplary manner even for Europe. He collected folksongs and tales by using from 1896 onward not only short-hand, but the phonograph as well. His accomplishments were recognised and considered worth following by the Ethnographical World Congress organised simultaneously with the World Exhibition of Paris in 1900 and also by Hungarian musicians like Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók and László Lajtha who set out on collecting expeditions under his guidance.

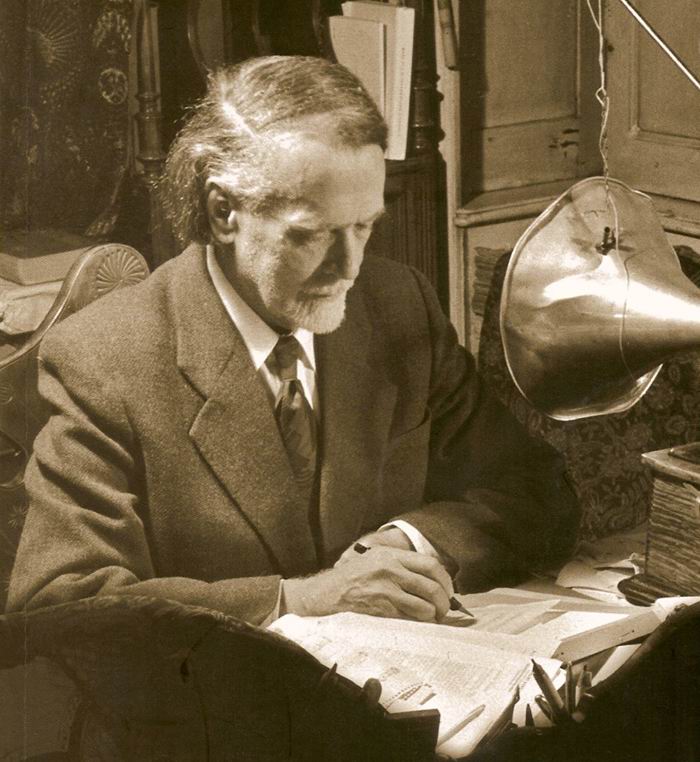

Phonograph recording „Rákóczi kocsmába” from Törökkopány, Hungary

Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967) listening to phonograph recordings

Photo: Károly Gink (MTI)

Among the Greatest of the 20th Century: Béla Bartók

Béla Bartók (1881–1945) ranks among the “three great” composers – Schoenberg, Bartók, Stravinsky – who had a decisive influence on the new music of the first half of the 20th century. No Hungarian artist with an oeuvre of national commitment has ever achieved greater international success.

|

|

|

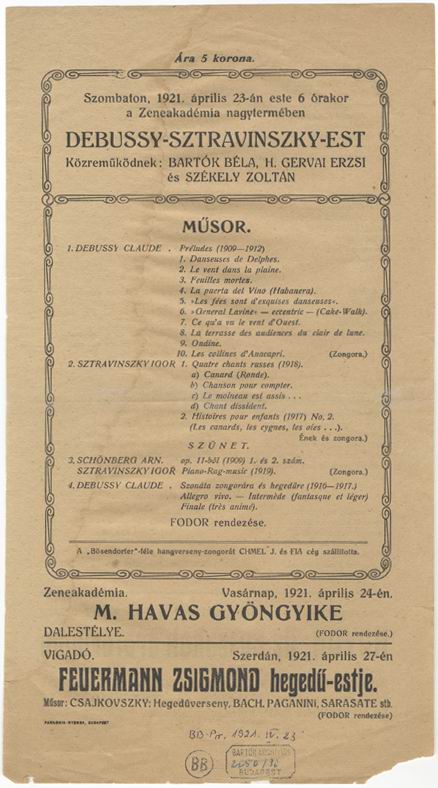

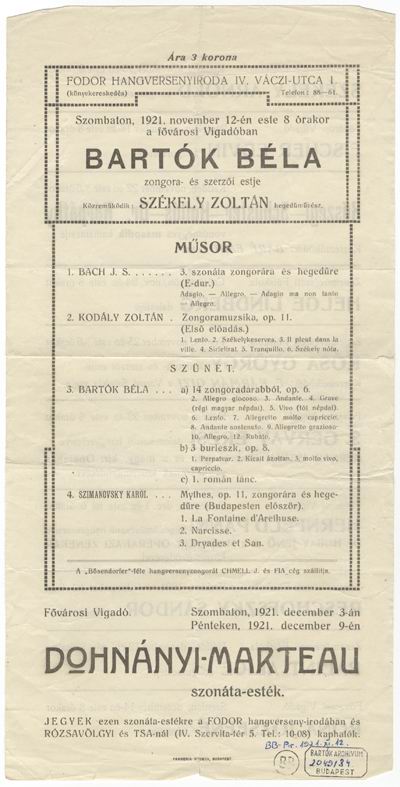

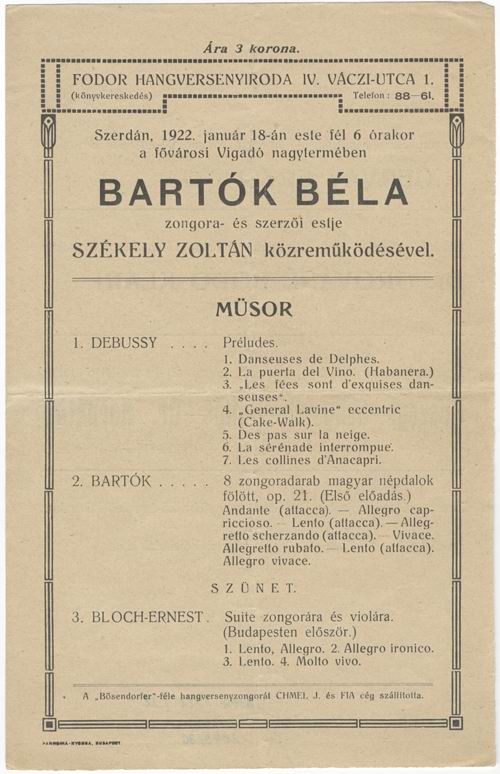

Bartók plays contemporary music in Budapest

Three original programme pages with Bartók’s entries

Budapest, HAS Institute for Musicology, Bartók Archives, 2050/30, 2049/84, 2049/86

Bartók: 14 Bagatell No. 2, Béla Bartók (Hungaroton)

National Character – Universal Value: Zoltán Kodály

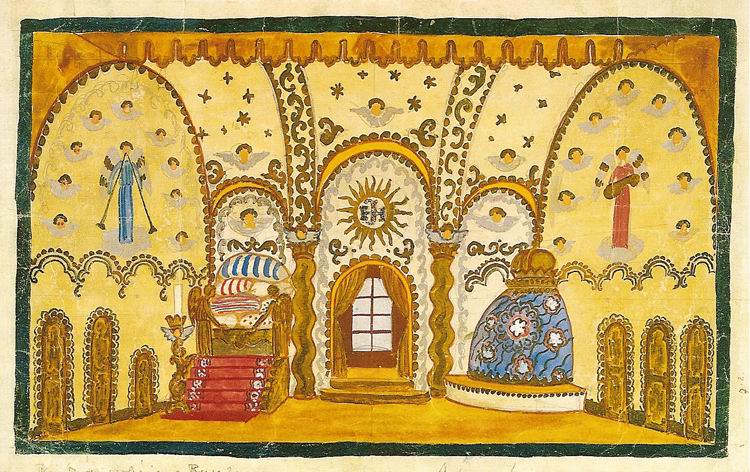

In the musical comedy Háry János historical reality and the people’s imagination mix; their unity is brought about by folksongs, heard for the first time on the operatic stage. According to Kodály the hero is “the Hungarian story-telling imagination come to life”. Kodály prepared a suite of six movements from the orchestral pieces, which is one of his most widely performed works.

“Háry’s room in the Burg”, Stage design for the first performance of Háry János at the Opera House by Gusztáv Oláh (1901–1956)

Budapest, National Széchényi Library, Theatre Division, KE 90

Hungarian Artists at Home and in the World

Hungarian music and Hungarian performers are recognisable, characteristic and competitive. The political conditions of today and the concomitant factors of an ever widening yet shrinking international world make people slowly forget the dilemmas and tensions of the past combined with the decision whether to go abroad or stay in Hungary, whether to emigrate, versus the moral imperative “you must live and die here”. All these phenomena have given place to a much more general, common desire: to live in a healthy spirit on the well-preserved earth with the music of Bach and Mozart, Liszt and Bartók, if possible. The Hungarian musician of today’s generation represents this objective, on whichever continent he may live.

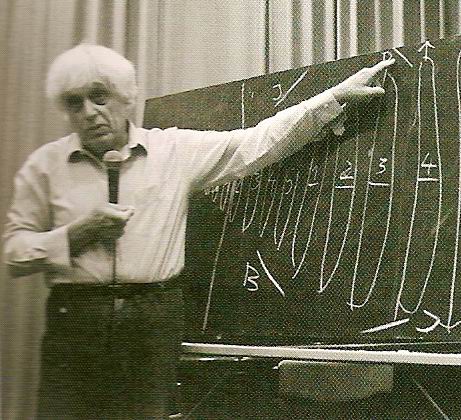

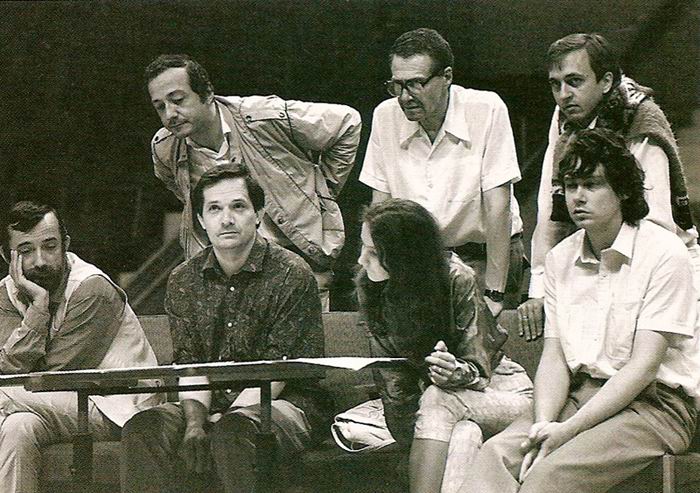

György Ligeti (1923–2006) teaching

Photo Kálmán Garas

The Bartók Seminar in Szombathely was created in the sixties with the assistance of the excellent violinist Ede Gertler, a contemporary of Bartók, its aim being to create an international haute école of Bartók interpretation. In the course of time the successful seminar developed into a workshop and festival of contemporary music devoted not only to Bartók’s music, but the music of the entire 20th century. This picture was taken at an important moment in the history of the festival.

Péter Eötvös (1944), Zoltán Kocsis (1952), Miklós Perényi (1948), György Kurtág (1926), Imre Rohmann (1953), László Vidovszky (1944), Adrienne Hauser at the Bartók Seminar in Szombathely, 1986

Photo Kálmán Garas